Understanding Mast Cell Activation Syndrome: Symptoms, Triggers, and Management Strategies

By Dr. Shawn Bladel | July 9, 2025 | Recreated Health

In the world of natural healthcare, one condition is gaining more attention for its complex, wide-ranging symptoms and its connection to chronic illness: Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS). This condition, often misunderstood or misdiagnosed, can cause a cascade of inflammatory reactions in the body, leaving individuals frustrated, exhausted, and searching for answers.

At Recreated Health, we believe that knowledge is power. Understanding MCAS through a natural lens can help patients take informed steps toward healing—gently, holistically, and sustainably.

What is Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS)?

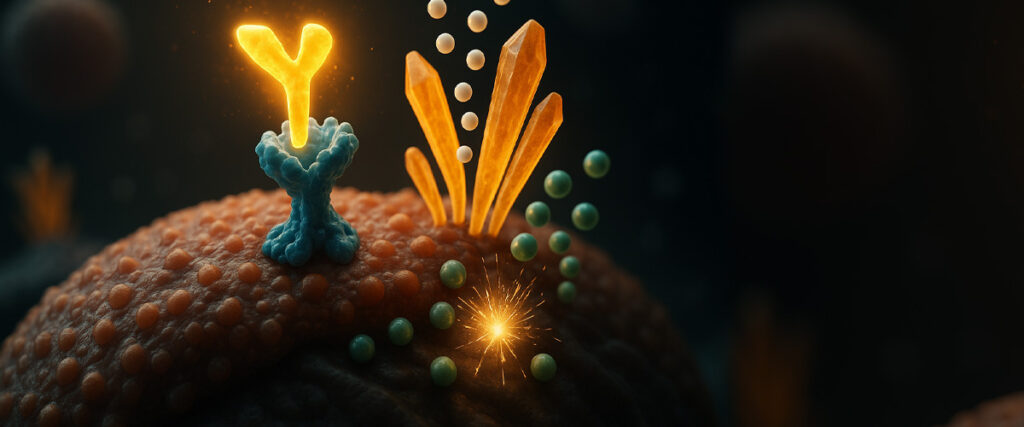

Mast cells are a type of white blood cell that play a central role in your immune system, particularly during allergic reactions and inflammation. These cells release chemical messengers like histamine, prostaglandins, and cytokines—substances that are necessary for fighting infection but can become harmful when overproduced or released inappropriately.

MCAS occurs when mast cells become hyperresponsive, releasing their contents excessively in response to triggers that may seem harmless. This overreaction can cause a wide range of symptoms that often mimic other conditions, making it difficult to diagnose1.

Think of mast cells as the body’s alarm system. In MCAS, the alarm is constantly blaring—even when there’s no emergency.

Symptoms of MCAS

MCAS symptoms vary greatly from person to person and can affect nearly every system in the body. This wide range of effects is why MCAS is often called a “great mimicker,” frequently going undiagnosed for years.

Skin and Histamine-Related Symptoms Include:

- Itching, hives, rashes

- Flushing or redness

- Swelling (especially after insect bites or food)

- Eczema or psoriasis flares

Gastrointestinal symptoms are also common, and could include:

- Bloating, gas, or cramping

- Diarrhea or constipation

- Food sensitivities or intolerance (especially to histamine-rich foods)

- Nausea or reflux

Additionally, respiratory manifestations such as wheezing, shortness of breath, and sinus congestion can resemble asthma or seasonal allergies, while cardiovascular symptoms like palpitations, rapid heart rate, and dizziness may be triggered by food or environmental exposures.

Neurologically, patients report brain fog, migraines, insomnia, anxiety, and mood instability. Other systemic issues include fatigue, joint pain, muscle aches, and irregular menstrual cycles2.

How to Recognize If You Might Have MCAS

If you experience multiple unexplained symptoms across different body systems, especially if they fluctuate with stress, diet, or environmental changes, MCAS could be a key contributor.

Many patients with mold toxicity, Lyme disease, or long COVID also develop MCAS as a secondary condition.

Triggers of Mast Cell Activation

Identifying personal triggers is essential in managing MCAS, and while they vary among individuals, most fall into four broad categories.

1. Environmental Triggers

Mast cells are sensitive and can be activated by chemicals and substances in your surroundings, including:

- Fragrances and perfumes

- Mold and mycotoxins (very common)

- Pesticides or cleaning agents

- Temperature changes (heat, cold, humidity)

- Pollens and airborne allergens

- EMFs (electromagnetic frequencies) for some sensitive individuals

For sensitive individuals, these environmental exposures can significantly worsen symptoms, which is why we recommend using a high-quality HEPA air purifier, low-toxicity cleaning products, and mold remediation, if needed, as foundational steps in an MCAS-supportive environment3.

2. Dietary Triggers

Certain foods are naturally high in histamine or can stimulate histamine release. The most common offenders include:

- Aged or fermented foods (cheese, wine, kombucha)

- Leftovers or slow-cooked meats

- Vinegar, pickles, or soy products

- Tomatoes, avocados, eggplant

- Spinach, strawberries, bananas

- Alcohol and caffeine

For MCAS sufferers, adopting a low-histamine diet, completing a food sensitivity panel, as well as using natural antihistamines like quercetin and vitamin C can be important initial steps in achieving relief4.

3. Emotional and Physical Stress

Both physical stress (like infections or surgeries) and emotional stress can act as triggers for mast cell activity. Overexertion, poor sleep, chronic emotional strain, and hormonal shifts (such as menstruation or menopause) often lead to increased symptom flares.

Supporting the nervous system through vagus nerve stimulation, breathwork, adaptogenic herbs, and grounding practices is a cornerstone of natural MCAS recovery5.

4. Infections and Biotoxins

MCAS is often secondary to deeper immune stressors such as chronic Lyme disease, Epstein-Barr virus, or mold toxicity. These infections and biotoxins overstimulate the immune system, leading to mast cell dysregulation over time.

Addressing these root infections requires a detoxification-first approach to avoid worsening symptoms. Drainage and immune support are essential to gently reduce the body’s reactivity while addressing underlying causes6.

Natural Management Strategies for MCAS

Healing from MCAS requires a layered, bio-individual approach. At Recreated Health, our goal is to support the body’s innate healing intelligence through detoxification, nourishment, and resilience-building.

1. Stabilize Mast Cells Naturally

Certain nutrients and plant compounds help regulate mast cell activity and histamine response:

- Quercetin is a powerful flavonoid that stabilizes mast cells and reduces histamine release7.

- Vitamin C acts as a natural antihistamine and supports immune modulation8.

- DAO (Diamine Oxidase) is an enzyme that breaks down histamine in the gut and can be taken as a supplement during meals.

- Luteolin is another flavonoid that reduces neuroinflammation and mast cell activity, particularly in the brain.

We often recommend using a combination of these, tailored to your symptoms and sensitivities.

2. Support Detoxification and Drainage

Impaired detoxification can cause histamine buildup and worsen MCAS flares. Supporting liver, lymphatic, and bowel function is essential. Gentle binders like CellCore’s BioToxin Binder, castor oil packs over the liver, and lymph-stimulating practices like dry brushing or using a vibration plate are helpful strategies.

Always open drainage pathways before beginning deeper detoxification—this reduces mast cell aggravation and improves outcomes9.

3. Regulate the Nervous System

Your nervous system and immune system are intimately connected. Calming the autonomic nervous system reduces inflammation and mast cell reactivity. Vagus nerve exercises, breathwork, cold exposure, gentle yoga, and trauma-releasing practices can create the internal safety required for healing.

We also use adaptogens like ashwagandha and calming nutrients such as L-theanine or GABA to help the body shift out of fight-or-flight.

4. Heal the Gut and Restore the Microbiome

Over 70% of mast cells reside in the gastrointestinal lining. A disrupted gut contributes directly to immune hypersensitivity. Healing the gut with soothing nutrients like L-glutamine, aloe vera, and short-chain fatty acids can lower mast cell activation.

Histamine-lowering, spore-based probiotics are often better tolerated than fermented varieties, which may exacerbate symptoms in histamine-sensitive individuals10.

5. Partner With a Skilled Practitioner

Because MCAS overlaps with so many other chronic conditions, it is vital to work with a practitioner experienced in complex root-cause healing. Dr. Shawn Bladel regularly sees MCAS in patients with mold illness, Lyme, long COVID, and chronic fatigue—and uses a systems-based approach to identify and treat the deeper dysfunctions.

“MCAS is often the result of deeper dysfunctions—mycotoxins, stealth infections, or a dysregulated nervous system. We use targeted testing and natural strategies to bring the body back into balance.” — Dr. Shawn Bladel

Conclusion: A Hopeful Path Forward

Mast Cell Activation Syndrome may feel overwhelming, but it is manageable—and even reversible—with the right tools and strategies. By identifying your unique triggers, supporting detoxification and the nervous system, and using natural stabilizers and gut support, you can take back control of your health.

References

- Afrin, L. B., et al. (2020). Diagnosis of mast cell activation syndrome: a global “consensus-2” effort. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, 8(9), 3122-3130.e1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7763504/

- Weinstock, L. B., et al. (2021). Mast cell activation symptoms are prevalent in Long-COVID. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 112, 217–226. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9360161/

- Brewer, J. H., et al. (2013). Detection of mycotoxins in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Toxins, 5(4), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins5040605

- Maintz, L., & Novak, N. (2007). Histamine and histamine intolerance. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 85(5), 1185–1196. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1185

- Tracey, K. J. (2002). The inflammatory reflex. Nature, 420(6917), 853–859. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01321

- Shoenfeld, Y., & Agmon-Levin, N. (2011). ‘ASIA’—Autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants. Journal of Autoimmunity, 36(1), 4–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2010.07.003

- Mlcek, J., et al. (2016). Quercetin and its anti-allergic immune response. Molecules, 21(5), 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21050623

- Johnston, C. S., & Huang, S. N. (1991). Effect of ascorbic acid nutriture on blood histamine and neutrophil chemotaxis in guinea pigs. The Journal of Nutrition, 121(4), 559–564. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/121.4.559

- Schmid-Schönbein, G. W. (1990). Microlymphatics and lymph flow. Physiological Reviews, 70(4), 987–1028. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.987

- Choi, Y. J., et al. (2019). Probiotic supplementation and immune modulation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Research, 11(2), 166–178. https://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2019.11.2.166